Local Sentō, a Surviving Tradition

Original essay published in the catalogue for Steam Dreams: The Japanese Public Bath.

By Eloise Rapp and Simonne Goran

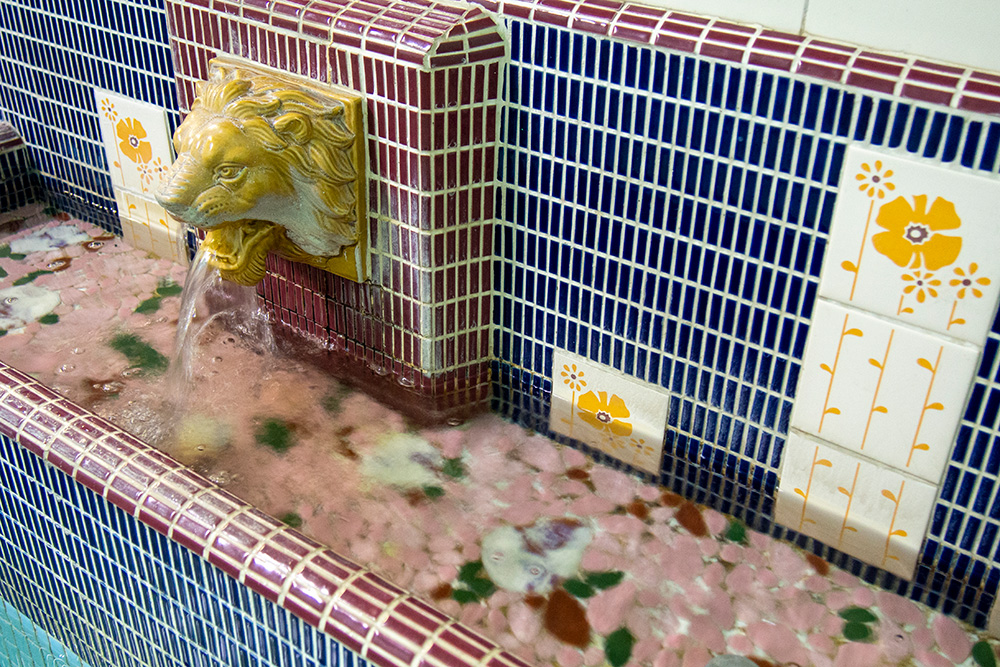

Our visit to the local bathhouse begins in a residential neighbourhood of a Japanese city. It is a winter’s evening and you’re surrounded by the gentle buzz of commuters making their way home. As you weave your way through narrow streets, past the fluorescent lights of vending machines and seven-elevens, you’re searching for a particular visual cue. You turn a corner and spot it—a temple-like awning nestled in a suburban block. A tall, thin chimney ascends from the rear of the building and a warm light spills onto the street from the entrance. As you pass through a decorative dividing curtain called noren and into the genkan (entryway) beyond, you feel as if you are leaving the outside world behind. The light from inside is now brighter, flickering through textured glass doors with the silhouettes and murmurs of customers coming and going. Colourful mosaic tiles are smooth underfoot as you slip off your shoes and place them in a tidy wooden locker. When you slide the door open an attendant greets you, perched high atop a wooden counter called bandai. They collect your entry fee and welcome you inside with a nod towards the changerooms.

The ceiling is lofty and the bamboo matting warm underfoot. A TV is stationed high in a corner, supplying the changeroom with the low-volume entertainment of an evening variety show. You exchange a friendly greeting with fellow bathers, who are trickling in after work or dinner. With your clothes tucked into a basket and deposited into a locker, you head into the bath area. Steam envelops you as you settle into a wash station. After scrubbing yourself clean, you select a bubbling pool and carefully ease yourself into hot water. Muscles relaxing, you exhale deeply, the troubles of the day leaving your body to join the warm vapour in the air. This is sentō—the local bath.

As part of a drive to preserve the rich culture and history of sentō, a new generation of artists, researchers and enthusiasts are working to resurrect the cultural practice of public bathing. The Steam Dreams: The Japanese Public Bath exhibition brings together Japanese artists, community members, university associations and museums, who are actively advocating for the continuation of local sentō. For them, the local bath is a crucial part of Japan’s social fabric—a tradition worth savouring in an ever-evolving cityscape.

Steam Dreams explores the history of sentō, with a particular focus on its preservation and the future of communal bathing. The exhibition highlights how the public bath developed, from early ideas of ritual purification to later cultivating a sense of place and community. In particular, Steam Dreams celebrates the unique design elements of the Japanese public bathhouse, from the glorious hand-painted murals of Mt Fuji waterscapes, to sentō’s charming utilitarian objects. Through a diverse selection of works, including historical artefacts, retro-pop ephemera, mural painting, contemporary photography, illustration and local community art, Steam Dreams presents an introduction to the multifaceted sentō culture of Japan.

Sentō through the ages

The custom of communal bathing has its origins in the spiritual world. The rise of Buddhism in the 6th century saw the establishment of bathhouses as a space for monks to physically and spiritually cleanse. These spaces were called yokudō or ‘bathing halls’. After a time, the yokudō were opened to the sick and the poor and eventually adopted by the general public.

The architecture of sentō has naturally evolved over several hundred years, from the windowless, closet-like steam rooms of early temples to the plumbed and boiler-heated structures of today. What hasn’t changed is the understanding of bathing as a regenerative ritual, capable of washing away more than a day’s grime.

Sentō use rose in popularity in the decades following WWII and peaked in the 1960s, when many people still didn’t have a bath of their own. However, following the wave of technological development that accompanied the 1964 Tokyo Olympics, the prefab ‘system bath’ or ‘unit bath’ began to take over. As the plumbed, all-in-one home bathroom became fashionable and affordable, the popularity of neighbourhood facilities slipped into decline. This shift, along with the emergence of ‘super sentō’ complexes that offered a bathing experience more akin to visiting a theme park, saw numerous sentō shut their doors. Over the years, countless traditional bathhouses have quietly faded away, becoming emblems of another time.

Today, in sentō that remain, you are likely to glimpse details that hark back to the local baths’ spiritual past, from the traditional noren split curtain at the entrance, to the deity-like animal hot water spouts. The owner may display a kakejiku (hanging scroll) with a favourite Buddhist mantra, or you may find a statue of the wealth-attracting tanuki, a folkloric character that keeps watch by the front gate.

At a popular onsen in Hakone, the sauna has a sign over its small wooden door reading mushin-dō, or ‘mindlessness hall’. The name references a Buddhist state where one’s mind becomes clear and mutable.This invitation to free yourself from intrusive thoughts may explain the recent re-kindling of interest in sentō. Whilst there is still a small but loyal patronage from elderly residents, a growing number of younger enthusiasts are coming to recognise sentō’s therapeutic effects.

A microcosm of Japanese society

As civic facilities sentō are clean, safe and unpretentious. They provide an atmosphere that is at once calming and invigorating, intimate and social. The public bathhouse is a space that unites community, where for centuries locals have gathered to relax, exchange news and enjoy quiet banter.

As Yoshiko Yamamoto and Bruce Smith observe in their book The Japanese Bath, “public baths in Japan form bonds of closeness among residents of the neighbourhoods they serve.” For elderly members of the community, the local sentō can be a lifeline. In larger cities such as Tokyo and Osaka, many senior citizens live alone in small apartments with limited opportunities for socialisation. Sentō provide an opportunity to talk with others and look after their health. This is the generation that grew up with sentō as a cornerstone of daily routine, so a visit to the local bathhouse evokes a sense of familiarity and comfort.

The atmosphere of sentō differs from that of the more upscale, resort-style onsen that were developed around natural hot springs. Local bathhouses tend to be homely and familiar, often with a delightfully nostalgic interior. Rarely will you come across digital devices or slick minimalist furnishings. Instead, you’ll find ephemera that recall a more domestic kind of bliss. Seiko wall clocks and ads for beauty products dot wood-panelled walls. Post-soaking refreshments of beer or flavoured milk are stacked inside a tiny café-style fridge, and you might find a decommissioned massage chair or mechanical weight scale languishing in a corner. Sentō are shrines to simple instruments of comfort and convenience—many of which you will see in Steam Dreams.

Steam Dreams: Bath artefacts on display

This exhibition traces the progression of Japanese bath culture from over 150 years ago to today, including design transitions from wooden to tiled floors, the implementation of a gender division, and the visual connection to nature achieved through mural artistry. Historical photographs from the Duits collection depict the evolution of the public bath from the late 1800s to the mid 1900s. The distinct architectural and atmospheric qualities of sentō today are captured by Kōtaro Imada in his photographic work. Artist and head of well-known Tokyo sentō Kosugi-yu, Honami Enya offers a glimpse into daily sentō life with intricate watercolour illustrations that draw on the bathhouse’s architectural blueprint.

The exhibition is framed by a younger generation seeking to inherit antiquated craft skills before sentō are rendered obsolete. Out of the three remaining masters, Mizuki Tanaka is Japan’s youngest and only female mural painter active today. With her murals, Tanaka is attempting to revitalise a practice traditionally occupied exclusively by men. The mural commissioned for this exhibition is a humble gesture to Tanaka’s expansive paintings that impress the walls of sentō across Japan.

Another artist, Toshizō Hirose, uses the long-established technique of hanko (stamp)-making to create designs signifying the unique features of every sentō he visits across Japan. Hirose has also created a new hanko for this exhibition and it is on offer for attendees to use as the instigator for their own sentō pilgrimage.

Revival, restoration, preservation and future-thinking are key references for Steam Dreams artists. These themes are reflected in the objects rescued from demolished or soon-to-be closed sites. The Bunkyo Youth Society of Architecture collection offers various sentō ephemera, many of which are still in use today. The Mosaic Tile Museum, Tajimi collection displays fragments of tiles of historical significance, as well as tile samples illustrating past design trends. New and old artefacts further highlight ongoing artisanal practices that produce painstakingly handcrafted objects for the communal bath.

Finally, the living and thriving local sentō community is represented by Steam Dreams. Katsura-yu, an unassuming but much-loved public bath located in a quiet neighbourhood of Kyoto, has contributed a series of handmade tiles that normally adorn their change room ceiling. Created by both the owners and their customers, the cheerful ‘Yu’-themed art tiles encapsulate the true essence of sentō today—community, continuity and unpretentiousness.

Steam Dreams: Reading material

The text collected in this publication offers a unique range of focus areas, bringing together four distinct perspectives from individuals working in and around the world of sentō.

Nodoka Murayama, Curator at the Mosaic Tile Museum, Tajimi writes about the rich history of tiles used in bathhouses, providing insight into how they have proliferated and changed over time.

In ‘The Preservation of the Sentō, an Urban Communication Hub’, Haruka Kuryu reflects on sentō as a residential safety net and place of connectivity and details the archival and preservation work of Bunkyo Youth Society of Architecture.

As an official ambassador for the National Sentō Association, Stephanie Crohin provides unique insights into the cultural and social aspects of bathing. She shares these with us in her essay, ‘The Art of Bathing in Japan’.

Reprinted in this publication is also the ‘Overview’ from How To Take A Japanese Bath, a poetic instructional guide by artist, writer and aesthetics expert Leonard Koren.

A selection of drawings from the original book by manga artist, painter and illustrator Suehiro Maruo are also featured.

Steam Dreams and, by extension, this exhibition catalogue, invite you to contemplate how Japanese public bathing has evolved over time, surviving the perpetual currents of change. Will sentō continue adapting to new culture? We are excited to bring together a community of people who strive to remember this time-honoured practice by surveying its rituals, etiquette, design and social impact. With Steam Dreams, we contemplate the past whilst looking to the future of sentō—whatever it may hold.